In this inaugural issue of The Digital Review, the editors have curated a collection of works that help us recover a mode of digital writing that was prominent in the early days of the web: the born-digital essay. The revival of this multi-modal essayism is central to this journal's creation in 2020. It is an effort to bring back attention to the personal, idiosyncratic, provocative and experimental forms that fuse “the digital” — discrete, deterministic, algorithmic, constrained — with “the essayistic” — digressive, liminal, wavering, exploratory.

Despite the categories in which new and invasive algorithms wish to place us and our ideas, the world and subjectivity is and always has been in a state of flux. The essay, a form without form as exemplified in Montaigne, Bacon, Emerson and countless essayists that come after them, asks us to acknowledge the flux. Not as a metric. And not as an answer to a question, but as the fount of further questioning. The complexity of the world in the summer of 2020 is self-evident in the streams of language and images that simultaneously awe, shock, soothe and incite. This is the human situation. The essays in this issue, all quite distinct in expression and in questions asked, are nonetheless written, self-consciously under constraint. Each one embraces and brings forward, rather than suppresses the digital constraint applied in design and computation. And yet within the formal boundaries, these digital essayists propose ambiguities to contemplate: games that look beyond winning and losing, simulations that critique easy access to a “real”, reflections on the indeterminate processes of digital creation and multimodal probes of language itself.

--Will Luers, Editor

Rediscoveries of electronic literature are no different than rediscoveries of print literature. Without structured acts of rediscovery, the works that shape a given era can easily be lost - and this is even more the case for a digital canon whose platforms are changing all the time. The editors of The Digital Review nod to David Madden and Peggy Bach, who asked important writers of the 1970s and 1980s to select, and write about their favorite works of neglected fiction. The Digital Review and the Electronic Literature Lab will be doing the same, over the current decade, for at least a few (of the thousands?) of forgotten digital works.

How do we maintain accessibility to born digital literary art amid hardware and software upgrades and changes to storage and presentation modes? This is the problem we seek to solve with the Electronic Literature Lab (ELL).

We view maintaining accessibility to mean a variety of activities a variety of activities that includes, of course, preservation, but we argue that it can also involve many others. For example, we host live events, like Live Stream Traverals, that expose contemporary audiences to works they cannot ordinarily experience due to outmoded software and hardware. It means we create exhibits that bring works to the public to be experienced and studied. We build repositories, archives, and collections, like the ELO Repository, to archive works and organize them based on specific criteria. We also interpret accessibility to mean that we document works in scholarly databases, such as ELMCIP and the ELD, and through scholarly writing, such as Rebooting Electronic Literature, Volume 1 (2018) and Volume 2 (2019). It means that we reconstitute web environments, including the trAce Online Writing Centre and The Progressive Dinner Party, and recover works like the those published in the six issues of the frAme journal. Finally, it means we restore outmoded works like Deena Larsen’s kanji-kus.

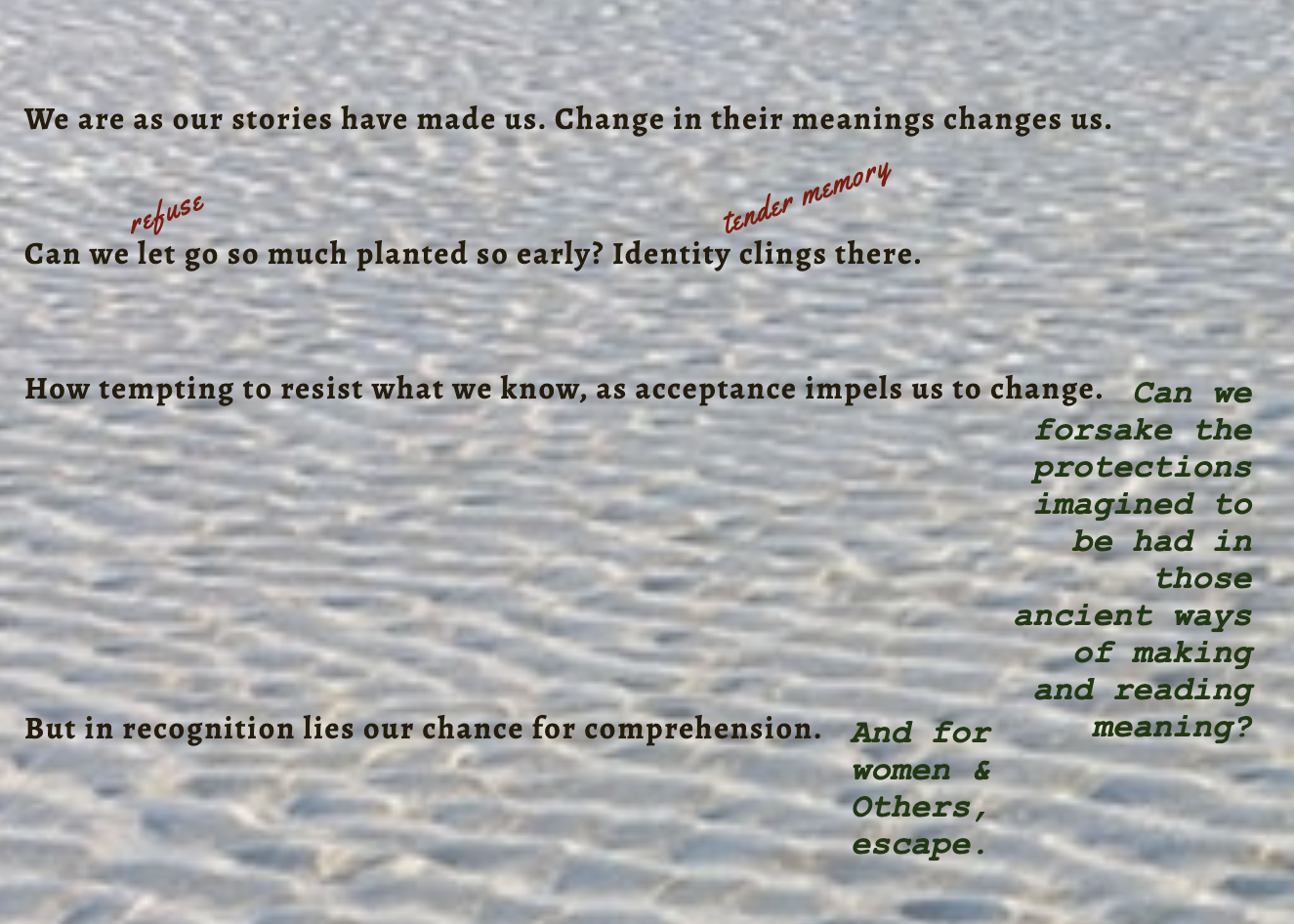

A recent project that speaks to our interest in maintaining accessibility through restoration is Annie Grosshan’s nonfiction essay, The World Is Not Done Yet. Her essay was created in Adobe Muse, which is no longer supported as of March 2020. For fear that over time the work would deprecate, Grosshans reached out to several folks, including Amaranth Borsuk, who recommended that she get in touch with the lab. The ELL Team explored various preservation strategies, including capturing the work via Rhizome’s Webrecorder and reworking the existing code. However, Muse produced code that did not consider responsive mobile screens, global styling, ADA compliance or SEO, and used proprietary MuCow (Muse Configurable Options Widget) for audio delivery and text animations. After close to two months of wrangling the very inelegant code behind the Muse program, we made the final decision to rebuild the work from the ground up in HTML5, CSS3, and JavaScript. The project was completed on May 27, 2020 and has been submitted for exhibition at the ELO 2020 and ICIDS 2020 conferences, as well as to the Electronic Literature Collection 4.

Poet Charles Bernstein's multimedia hypertext essay, An Mosaic for Convergence, was written in 1997. Because it was made in HTML and JavaScript (with the help of Dante Piombino), it was far easier to reconstruct than some other works. And yet, just a few lines of obsolete code made the work inoperable on most contemporary browsers. The restored work was republished in 2019 in the electronic book review and again here as an important "rediscovered" digital essay.

ELL is not about simply saving things but providing a way for the genius of human expression to live on through time. At the heart of what we do in ELL is preserve humanity, particularly the humanity living and working in the late 20th and early 21st centuries to create born digital literary art.

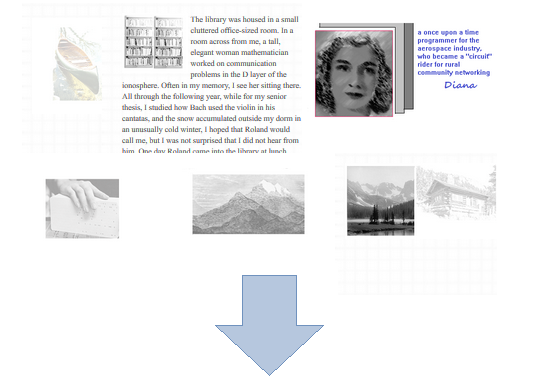

Annie Grosshans’ personal narrative, The World Is Not Done Yet is a “weblication of theoretical poetics,” originally produced with Adobe Muse in 2013 and reconstituted in 2020 in HTML5, CSS3, and Javascript by members of the Electronic Literature Lab team.

Charles Bernstein's hypertext essay from ebr Issue 6 (1997-1998) is a web extension of the poet's "shuffle texts" - performed at readings in which he randomly selected a set of short poetic texts from a deck of cards. In this digital essay, pages are randomly selected with a "next" button. By the late 90s, Bernstein could sense a shift in literary sensibility, where it was beginning "to seem as natural to think of composing screen by screen rather than page by page."

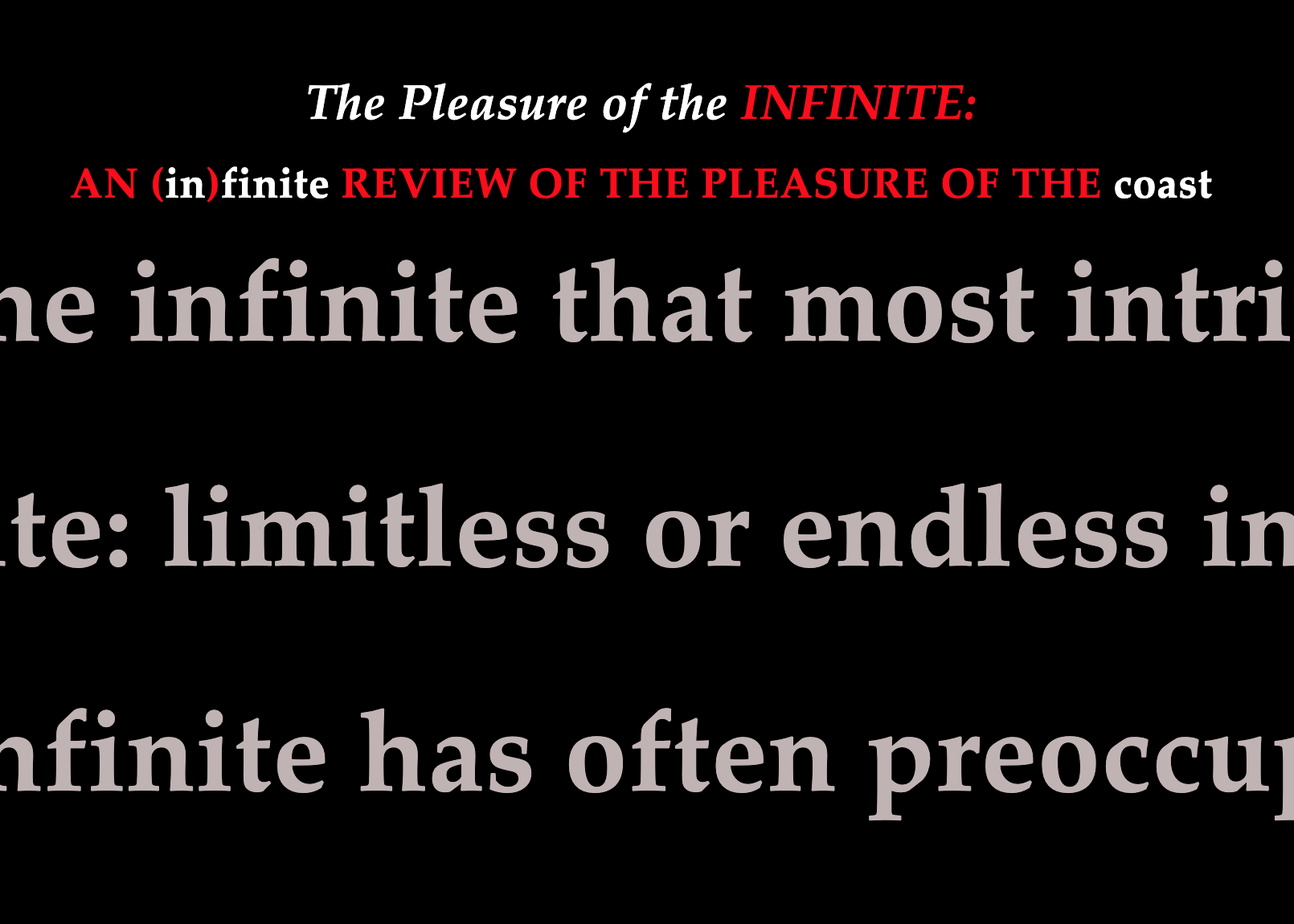

J.R. Carpenter’s hygro-graphic novel The Pleasure of the Coast is presented in five sections: ‘the infinite coast’, ‘the technical coast’, ‘the incremental coast’, ‘the grammatical coast’, and ‘the route of La Recherche’. In this review of Carpenter’s web-based work, David Thomas Henry Wright adopts Carpenter’s code used in ‘the infinite coast’ to produce an (in)finite review. Scrolling left or right indefinitely, this review explores Carpenter’s ‘infinite coast’ in relation to poetic and theoretical depictions of the infinite by Giacomo Leopardi and David Foster Wallace.

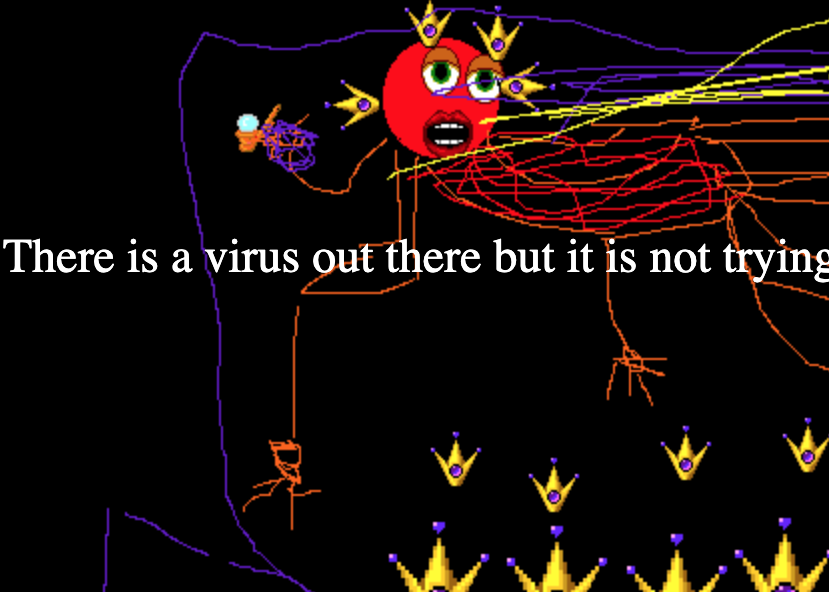

Blocked In is a hybrid Twine hypertext platformer videogame essay by Anastasia Salter and John Murray, published in Hyperrhiz’s special issue called “Buzzademia,” edited by Anne Cong-Huyen, Kim Brillante Knight, and Mark Marino. In his short review “Playing the Hard Questions,” Caleb Andrew Milligan discusses Salter and Murray’s videogame essay as a work of born-digital scholarship one can read and play. The review is an interactive experience Milligan made in Twine as a critical making response in kind to Salter and Murray’s Blocked In. It therefore puts into practice their claim that the future of games and game studies is one “we are defining through…not only what we play, but…most importantly what we make.”