Natural Disasters

Scientists find no link between coal, climate change and Australian Fires.

Author redacted

Date redacted

Governmentality plays an important part in the distribution and regulation of fake and misleading news. Predating the internet, Foucault’s theory focuses on how power is exercised, instead of how it is distributed to members of government (1982). Foucault refers to governmentality as a code of conduct where governments draw on internal and external guidance (1982, 220; Methmann 2011). As a result, the control of populations “does not work through direct interventions, but lives by the 'creation of probabilities'” (Lemke as cited in Methmann 2011, p.72). One such way to create different probabilities is through the dispersal of fake news and misleading information.

The recent bush fires in Australia saw many calling out for goverment legislation on climate change (Shuttleworth 2020). Many scholars even cited the cause as global warming (Doherty 2020). This news made international headlines, with many calling for global reform before it’s too late (Shuttleworth 2020). However, no change was forthcoming from the Australian government where the crisis was playing out (Doherty 2020).

This brings up concerns over the unenforcable nature of governmentality on a global scale (Chandle, 2009; Joseph 2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c; Selby 2007). Governmentalty, the exercise of power, only actually works when two elements are present; a population to control, and a civil society willing to respond to goverment regulations and laws (Joseph, 2009; Methmann 2011). Methmann argues that both of these things are largely unseen outside of “advanced liberal societies” (2011, p.69) and the Western world (Methmann 2011; Joseph 2009). Even on an international level, state sovereignty still exists (Methmann 2011), to the degree that even the UN has few powers in enforcing the rules signatories agree to (Beaumont 2013). No form of international disciplinary power or international governmentality has worked on a global scale. As Foucault explains, governmentalisation of state has become the dominant way of exercising power in modern societies (Foucault 2007, 109). It isn’t easily transferable to a global population with different value put on civil obedience (Foucault 2007; Methmann 2011).

In making individuals behave, we also see the rise of biopolitical state racism, where “the body is caught up in a system of constraints, obligations and prohibitions” (Foucault 1977, p.11), and where control is used, not to protect a sovereign, but society at large (Foucault 1977, p.11). This results in state-racism, that is, those who submit to control are perceived as good, and those who defy it are bad (Foucault 1977). Examples of this can be seen in the unfairness of the criminal justice system, where bias unfortunately does sometimes become a deciding factor (Berk 2017). This can also be seen recently in the debate on climate change in Australia, with more and more in support of new measures, but few actually defying the system to act in support of their convictions. This is because much of the debate around climate change requires people to question the intangible and unquestioned parts of biopolitical power. Those whose attitudes have been shifting, are finding that the message given to them through biopolitical power is currently clashing with their sense of moral and legal obligation to the generations that will follow. Following Macdonnell, we might view this as “an effect of conflicts of discourses” (as cited in Fleming 2010, p.10).

In this sense, we use the word racism to mean exclusion, a way to differentiate those who are not catered for by biopower (Murray 2018). These races are often refugees, however, those resistant to biopolitics also fall into this category (Murray 2018). This has created a political minefield for governments as they need to support victims while also discrediting them. This is not only the case with the victims of Australian fires, but also numerous other natural disasters that came before them. The fires in Australia have highlighted this much bigger power struggle between nation states as they try to decide on a course of action for when disasters like this happen.

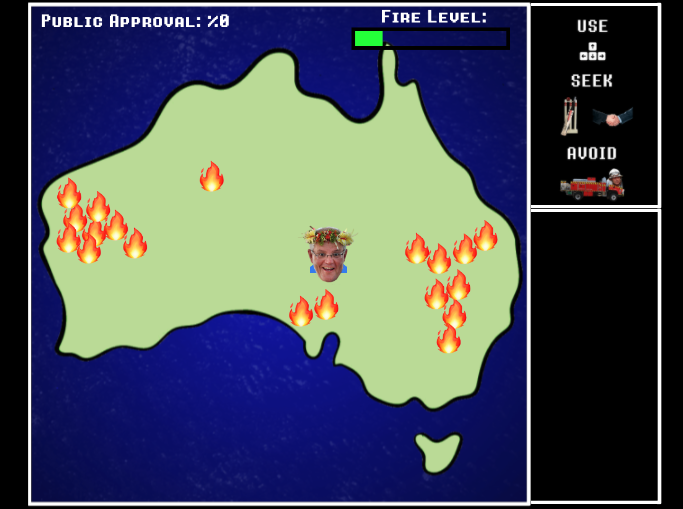

While not a work of electronic literature, the ScoMo Simulator is a good example of the power of digital media for political comment. It is one of many examples of user-generated content that resulted from Scott Morrison's handling of the Australian fire disaster. Users play as ScoMo, who takes the form of a floating head over Australia. They must stop wildfires, while avoiding the firetrucks and the firemen themselves. If users collect the handshake icon, they get a trip to Hawaii. This use of iconography and symbolic imagery to draw on cultural references and satire is also used in electronic literature (Pawlicka 2014) as well as metonymy and metaphor (Gennaro 2015; Hayles 2007).

Not sponsored

Not sponsored

About

AUTHOR WRITES GREAT THINGS: Local author writes next great work while in COVID19 quarantine.

About

MORE PEOPLE MAKING ART: More people are turning to art amid COVID19 social distancing restrictions.