Fake Data

Newly released emails prove that scientists have manipulated data on global warming. The data is unreliable.

Author redacted

Date redacted

Our focus on climate change has become a matter of survival, or rather, a question over whether or not our survival is at risk. Government inaction has been concerning for many as, according to Stern “climate change threatens the basic elements of life for people around the world – access to water, food, health, and use of land and the environment. (Stern 2007, 65). This makes climate change an important part of a government's strategy, as climate change threatens their control and hold of biopower, that is, the “regulation of life processes of living legal subjects” (Justice 2017, para.7). Justice suggests that “one can understand this to apply primarily to citizens living within that state, and possibly (and some would add ideally) also applying to other persons physically present within a state’s borders” (2017, para.7). Contradicting this is our understanding of the role of the state as “that of providing security for its population” (Justice 2017, para.7). John Locke likewise says the state has a duty to protect an individual’s right to life (1999).

This brings us back to the citizens being controlled, whose sharing of the many statements that form fake news are largely problematic, especially as they cross borders. To Foucault;

“not all regions of discourse are equally open and penetrable; some of them are largely forbidden (they are differentiated and differentiating), while others seem to be almost open to all winds and put at the disposal of every speaking subject, without prior restrictions” (1981, p.62).

In other words, scientific communities, and many examples of traditional media, are restrictive and need specific qualifications in order to participate. Many contemporary forms of media, largely as a result of web 2.0 and the rise of participatory culture, are much less restricted and controlled (Peters 2013; Hanusch 2017), and much easier to share globally. The question then becomes, should this dissemination of false information across borders be the responsibility of the governments these citizens belong to?

Not only is fake news a way to maintain control of resources, something climate change threatens, but the very act of creating fake news is much more profitable for the economy as there is less reporting and fact checking involved (Braun and Eklund 2019; Alcott and Gentzkow 2017, 217-221; Rubin,Chen and Conroy 2015; Creech and Roessner 2018). This, according to Jenkins, is the result of rapid technological change (2017). McLuhan’s 'the medium is the message' shows how technology has changed the environment around us, such as the the way the manuscript created the medieval world and printing the modern one (McLuhan 1994, p.6). “For the top news sites, social media referrals represent only about 10 percent of total traffic. By contrast, fake news websites rely on social media for a much higher share of their traffic” (Alcott and Gentzkow 2017, p.222). Jenkins suggests, instead of looking at the content of fake news, we look at the overall message, and that is one of fear for how quickly things are changing (2017). This fear is what is being leveraged by governments in their control and retention of biopolitical power, creating reassurance that nothing is actually changing. It’s this belief that many scientists are criticising and speaking out against. As Rubin, Chen and Conroy explain, “deceptive news can be harvested, crowdsourced, or mimicked by qualified study participants” (2015, p.3).

But is it ethical? Given that a lot of fake news comes in support of singular governments’ biopolitical systems, it is fair to say this isn’t ethical, as one nation’s biopolitics are being applied to another. Justice claims that the way information crosses borders should be regulated by the government in order to “ensure that the behaviour of its presently resident population does no harm to others, regardless of where the impacts of that behaviour occur” (Justice 2017, para.9). Our access to commoditised essentials, such as clean air and water, should be universal but, quite often, we see the morally ambiguous behaviours of one nation cross into others, thanks in a large part to the connectivity offered by the world wide web. An example of these impacts can be seen with the Cambridge Analytica scandal in the US, in which the Russian government was complicit ("Facebook Data Gathered by..." 2018). According to Alcott and Gentzkow, “the declining trust in mainstream media could be both a cause and a consequence of fake news gaining more traction” (2017, p.7). In the case of climate change, we see what was once a coded set of regional beliefs, get treated as universal truths (Foucault 1980). It is fair to say that we see a perceived relationship between scientific discourse and truth (Cazetta et al 2019) which we might believe believe makes it easier for us to tell the difference between real (i.e. true) and fake news. However, Foucault contradicts this, defining truth as “the assembly of procedures that allow everyone at every moment to make statements that will be considered truths” (as cited in Cazetta et al 2019, p.5). By thinking about truth as action, it becomes coded in cultural and political contexts relevant to where the scientific study is taking place and the ways in which that truth is communicated. A specific set of procedures for one state doesn't always translate across borders;

“As Foucault (1997) would argue, the strategic production of truth is rooted in the workings of institutional power, where those that can expertly navigate changing economic relations and technological possibilities then gain the means for controlling, if not what is true, then how it is understood as true” (Creech and Roessner 2018, p.275).

Electronic literature is an under-utilised medium for exploring these issues; “With recent discussions around ‘fake news,’ hijacked elections and the problems around data profiling, critical explorations of digital culture and text has become a central concern for contemporary democracy, education and libraries” (Pold 2019, para.1).

An example of electronic literature being used to question our use of data is The Listeners by John Cayley. The Listeners is a third-party app that replicates Amazon’s Alexa to explore surveillance in the home;

“The Listeners is a linguistic performance, installation, and Amazon- distributed third-party app or skill – transacted between speakers or speaker- visitors and an Amazon Echo...” (Cayley 2020)

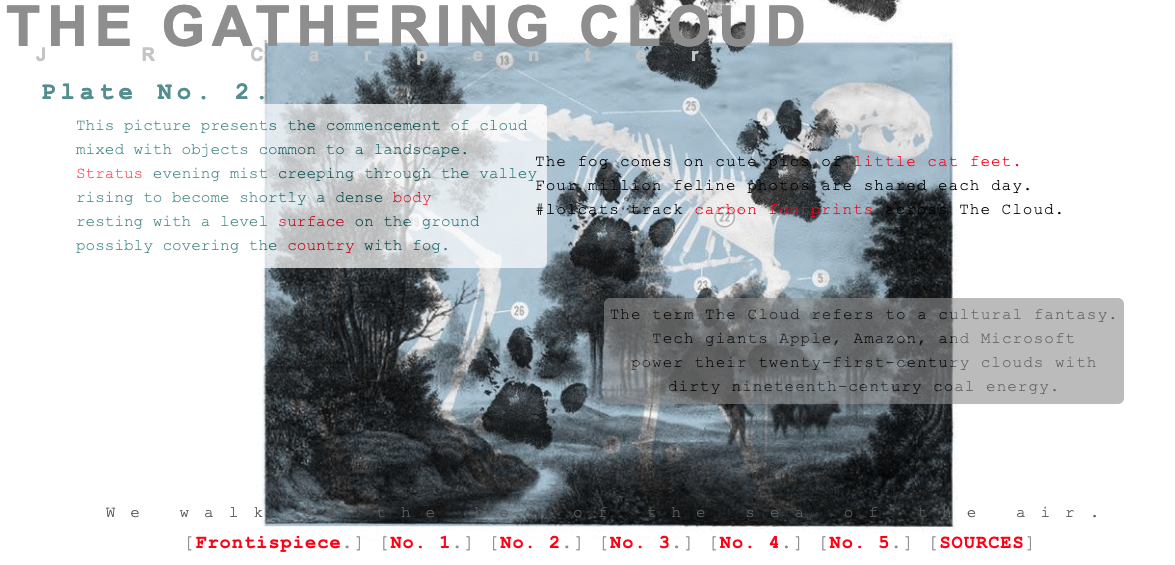

Another example is J.R. Carpenter’s The Gathering Cloud which utilises the cloud as a perceived infinite resource. In this work, the cloud becomes a metaphor for the environmental impact of the digital computing cloud;

“many even see digital literature as an eyeopener on how online services such as Google and Facebook function and relate to contemporary discussions of ‘fake news’ or data profiling” (Pold 2019, para.2).

Not sponsored

About

AUTHOR WRITES GREAT THINGS: Local author writes next great work while in COVID19 quarantine.

About

MORE PEOPLE MAKING ART: More people are turning to art amid COVID19 social distancing restrictions.