And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind.

—Revelation 6:13

A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.

—Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

Fin du Monde is a darkly comic generative AI digital narrative that meditates on the popular fascination with disaster, mortality, and teleology through representations of an apocalyptic cataclysm that manifests as a global meteor shower impacting cities across the planet earth simultaneously. La Fin du Monde—the end of the world—is an unprecedented yet highly anticipated, much-feared, and always-already-narrativized event. The world’s ending or radical transformation resulting from a celestial impact event is one we know from our popular imagination.

We face many crises that offer us the spectre of humanity’s spectacular devastation, both via means produced by humanity itself, such as a nuclear war that seems more possible now than it has in a half century, anthropogenic climate change, or natural causes such as the eruption of a super volcano. Over the past several years, as we emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic, we were immediately confronted with Vladmir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and a brutal war in Europe that continues to the present day. I began working on the Fin du Monde project in October 2023, just as the Israel / Gaza conflict began to unfold.

During the same period, we have the rise of generative AI. Suggestions that we are approaching of the technological “singularity”—a point at which machine intelligence surpasses human intelligence—are open to debate. But generative AI is clearly in the process of transforming many aspects of our economy, culture, and society.

A growing part of this discourse concerns debates of “existential risk” or “x-risk,” which speculates that the coming apocalypse may be brought about by a malevolent, superintelligent AI that no longer perceives humanity as necessary. This scenario is taken quite seriously by many, including some leading figures in the tech industry. In 2023, the Future of Life Institute circulated a petition titled “Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter” that called on all AI labs to immediately pause training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4. It argued:

Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth, and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources. Unfortunately, this level of planning and management is not happening, even though recent months have seen AI labs locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one – not even their creators – can understand, predict, or reliably control.

The petition was signed by many figures who are themselves deeply involved in the development of AI. Although AI alignment and saftey concerns remain a matter of vigorous debate, there is no evidence that the Future of Life Institute letter had any impact on ongoing research to develop more powerful language models.

The narrative framing of Fin du Monde is quite simple: neither a human-caused apocalypse nor one brought about by a malevolent superintelligent AI have come to pass. Instead, an unanticipated, intense, and highly destructive meteor storm has impacted the planet. This event may or may not have eliminated human life from the face of the Earth.

Fin du Monde includes two narrative layers. The first is a series of large sets of DALL•E 3 generated images of the meteor storms impacting different cities and environments such as Washington D.C., Tibet, Chicago, London, Paris, and the International Space station. These images are represented here as video slideshows. The slideshows are accompanied by AI-generated musical soundtracks that relate thematically to the events and cultural contexts represented.

The second layer of Fin du Monde is a series of short newscasts distributed in the days, weeks, and months after the cataclysmic event has taken place. They are purportedly produced by a benevolent AI system trying desperately to locate human survivors and struggling with its purpose in the absence of human interlocutors. The AI newscasters depicted in the videos are neither malevolent, nor superintelligent, but they are confused. Electricity continues to power the server farms upon which they run, but the people who used to farm them and for whom they labored seem to have gone silent. The news broadcasts are human authored but produced with AI actors.

Transformer-based large language models manifesting in applications such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Bard, text-to-image generators such DALL•E 3 and Stable Diffusion, text-to-music generation systems such as Suno, and a coming wave of text-to-video generation systems such as Sora are already changing the way that write and create. These systems are not ideologically unproblematic, given the ways that the data that drives them was harvested, and the power relations embedded within them. Yet they are wonderous and powerful. It is a stretch to think of these systems as actually “intelligent” as the processes that drive them are essentially probabilistic. They operate differently from human cognition, as far as we understand it, yet they are cognitive machines that read, process, and respond to human input in a recursive cycle.

This human function in AI-driven creativity is the focus of my current research and creative practice. Humans converse with generative AI. We are tempted to anthropomorphize these systems. We write to them, and they provide helpful texts in response. We ask them for advice, and they give it. We prompt them with a description of an image, and they produce a visual output that in some way approximates it. They hack away at our ideas and respond to them as a somewhat knowledgeable conversation partner would. Yet the systems themselves do not work without the key function that humans provide, the writing that serves as input to these complex probabilistic language machines. They are nonconscious cognitive systems that interpret human writing and attempt to optimize the best average, and therefore coherent, response to it.

I argue AI text-to-image generation systems are writing environments, and that the images produced by interaction with these systems are themselves a form of writing in collaboration with a non-conscious cognitive system.1 The results of these interactions are postmodern pastiches of the language provided to the system by the human-written prompts that are transformed into images. I understand the output, the images themselves, to be a transcoded manifestation of writing.

This is not to say that what is outputted from DALL•E 3 has a direct and accurate denotative correspondence2 to the written text, the prompt, that the human writer provides. These systems are no pens or typewriters, but probabilistic cognizing systems that approximate. They approximate the probable meaning of the prompt the human provides, then approximate a probable response, and then map that response conceptually to the images within its training set, before producing an image based on that mapping. We can think of this as an operation that occurs within a vector space, in the latent space between labelled images that the system was trained on. The system is trying to average all the images attached to any given concept in the prompt and create an image that might be found in the imaginary space where all those concepts meet. In doing so, it pulls in various visual and conceptual referents to the language of the prompt.

It is important to note that stochastic elements are always involved, so there will always be some variability in the image delivered in response to a given prompt. Any time you type the word “lion” into the prompt window, a different lion will be generated in response. Of course, the user will typically be more specific. The system will then try to map these elements together in a kind of pastiche.

The operations of these models are not exclusively probabilistic. There are layers of mediation between the user and the image generation system, and between the output of the generation system and the user. DALL•E 3 is now embedded within ChatGPT, and rather than simply responding to the prompt provide by the user, DALL•E 3 first runs the user-provided prompt through a request to ChatGPT to write an optimized prompt to DALL•E 3.

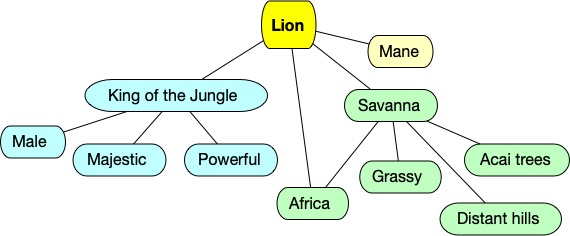

My prompt for “lion” became, in ChatGPT’s augmented version, “A realistic depiction of a majestic male lion with a full mane standing on a grassy savanna under a clear blue sky. The lion gazes intently into the distance, embodying the powerful presence of the 'king of the jungle'. The background features sparse acacia trees and distant hills, capturing the essence of the African savanna.”

“Steampunk lion” became “A steampunk-themed lion, combining Victorian-era aesthetics with futuristic elements. The lion has mechanical components visible under its skin, with gears and brass fittings. It features a mane made of copper wires and steam vents, with glowing amber eyes that look like small lamps. The setting is an imaginative steampunk environment with cogwheel trees and a backdrop of misty, industrial cityscapes under a cloudy sky. The overall color palette includes shades of bronze, copper, and muted golds, creating a rich, atmospheric scene.”

And the third, more detailed prompt became “A black and white photograph-style image depicting a steampunk lion wandering the streets of Victorian London on a rainy day. The scene captures the cobblestone streets wet with rain, with the lion featuring mechanical elements and a mane of gears and steam vents. In the foreground, a young girl dressed in a 19th-century tattered dress is selling matches, holding a box out to passersby. The setting includes gas lamps and fog, enhancing the Victorian atmosphere, and the overall mood is somber yet captivating.”

Even the very minimalist “lion” prompt is highly embellished by ChatGPT before it is channeled to DALL•E 3 and fed to the diffussion model. Common terms associated with the word “lion,” its average semantic neighbors, are pulled into the prompt, and some of those terms’ semantic neighbors are pulled in for further refinement.

The image becomes more complex in response to more articulated prompts. While the prompt author could strive to provide as much precision and detail as possible to generate an image that is extremely mimetic, each element provided to the system also introduces a new stochastic variable. In the first example we see a lion that looks roughly like we might expect a lion to appear, for example, in an illustrated encyclopedia. The second images blends the concept of lion with visual elements of steampunk, as it takes on gears and polished chrome limbs. By the third image, we are well within the zone of the postmodern. There are visual references that we might expect but there are also surprises: the lurking man in the background, the fact that matches the girl is selling are on fire, or that the system posits that the match seller must be selling the matches to the lion, perhaps because the lion was the only other figure mentioned in the prompt. Just as ChatGPT starts piling likely semantic neighbors onto the words that we provide it with, DALL-E•3 piles on visual cultural references that are coherent with parts of the prompt. This semantic coherence doesn’t necessarily imply logical sense. While typical images of matches are often seen on fire, Victorian match sellers would not typically sell them while they are aflame. We can assume that many of the images of matches in the image training data show matches that are on fire. At some point in the generation process, the system made a somewhat aleatory determination that the matches were on fire.

In another image generated from the same prompt, the matches are not on fire, though they are extraordinarily large matches sold and distributed in very large boxes:

The overall effect of these slightly mismatched visual references is absurd, at the same time as these layers of semantic neighbors at the levels of both language and visual culture begin to suggest a background narrative that might be more interesting than an average lion standing in a savannah, its average habitat.

The training data upon which generative AI text-to-image is based are replete with images of apocalyptic events. The scope of the training data used in OpenAI’s models is immense. Although OpenAI has stopped releasing detailed technical data, we know that the language training set for GPT-4 runs into the range of trillions of tokens, and DALL•3 is driven by billions or trillions of text-image pairs. Training data is both proprietary and contentious—most of the legal and ethical conflicts around contemporary generative AI involve questions of how consensually and legally the training data was collected. Regardless, for the purposes of the Fin du Monde project, one can safely assume that the OpenAI platforms access a vast swathe of our apocalyptic cultural imaginary. Fin du Monde is an attempt to access that cultural imaginary and represent it in digital narrative.

Writing with LLMs and text-to-image generators exposes a form of collective digital unconscious. Writing on AI generated images, Eric Salvagio notes that “machines don't have an unconscious, but they inscribe and communicate the unconscious assumptions that are reflected and embedded into human-assembled datasets.” The probablistic calcuation that is involved results in the generation of an image that is roughly the average visual estimation of the concepts described in a prompt. In his “Small History of Photography,” Walter Benjamin briefly described an “optical unconscious” as “another nature which speaks to the camera rather than to the eye: ‘other’ in the sense that a space informed by human consciousness gives way to a space informed by the unconscious.” Benjamin here isn’t getting wrapped up in the muck of the Freudian unconscious, but instead pointing out that there are details of any given moment that slip past our conscious minds during “the fraction of a second the when a person actually takes a step.” Benjamin argues that these details are “meaningful but covert enough to find a hiding place in waking dreams.” The photograph makes them “capable of formulation.”

By presenting us with an averaging of conceptual representations in visual culture, text-to-image generation similarly reveals a collective digital unconsious, a way of seeing what assumptions we culturally constructed even as they have become so transparent as to be invisible to us in our everyday lives. Of course, as Pasquinelli notes, the “use of anthropomorphic metaphors of perception to describe the operations of artificial neural networks […] is misleading. As is often repeated, machine vision ‘sees’ nothing: what an algorithm ‘sees’ – that is, calculates – are topological relations among numerical values of a two-dimensional matrix” (164-165). The aspects of an unconscious revealed by text-to-image generators lay not in an anthropomorphized intelligence within the system, which is only calculating averages and representing them as images. The digital unconscious is rather that of the society from which those images emerge.

There is no question that text-to-image generation reveals bias in the dataset that it is trained on. This is a particular concern of the Fin du Monde project. In the past this could be attributed to the limitations of a very large but nonetheless limited dataset. If ChatGPT were primarily trained on Reddit or 4Chan or Twitch video transcripts, we can predict that the discourse it produces would be shaped by that training and by the demographics of the groups that contribute to it. The limitations of a smaller dataset were evident in the performance of early large language models.

We can still attribute some biases to the limitations of the datasets of LLMs. ChatGPT and other prominent LLMs appear to be much better at framing their responses in the terms of the context of American culture than they are at doing so in context of less dominant cultures. This will be one of the primary foci of Jill Walker Rettberg’s Advanced ERC project AI Stories: Narrative Archetypes for Artificial Intelligence, which is investigating how LLMs are representing narratives within specific languages and cultural contexts. The Norwegian Research Council-funded project I’m leading, Extending Digital Narrative (XDN) is exploring generative AI as a narrative writing environment in order to discover what the constraints and affordances of these environments are, what new literary genres might emerge from their use, and how research creation can serve as a critical instrument for better understanding how these environments operate and what impacts they might have on how narratives operate in our culture. Both these projects are taking place in the context of the Center for Digital Narrative’s focus on digital narrativity. Algorithmic narrativity is the combination of the human ability to understand experience through narrative with the power of the computer to process and generate data (Rettberg & Rettberg 2024).

Even if GPT-4 and most of the other dominant large language models skew toward American (and arguably even more specifically Silicon Valley) ideology and cultural contexts, their training dataset is now so immense that it encompasses a very large portion of the human discourse that can be found on the internet. Its image training dataset is similarly massive. As described above, both LLMs and diffusion models are by their nature averaging machines. Because their training data is so encyclopedic, it may make more sense to stop thinking about the bias within the training data and instead begin thinking about how they reveal biases within Western culture more broadly, a mass digital unconscious, a collective imaginary that reveals our biases and norms.

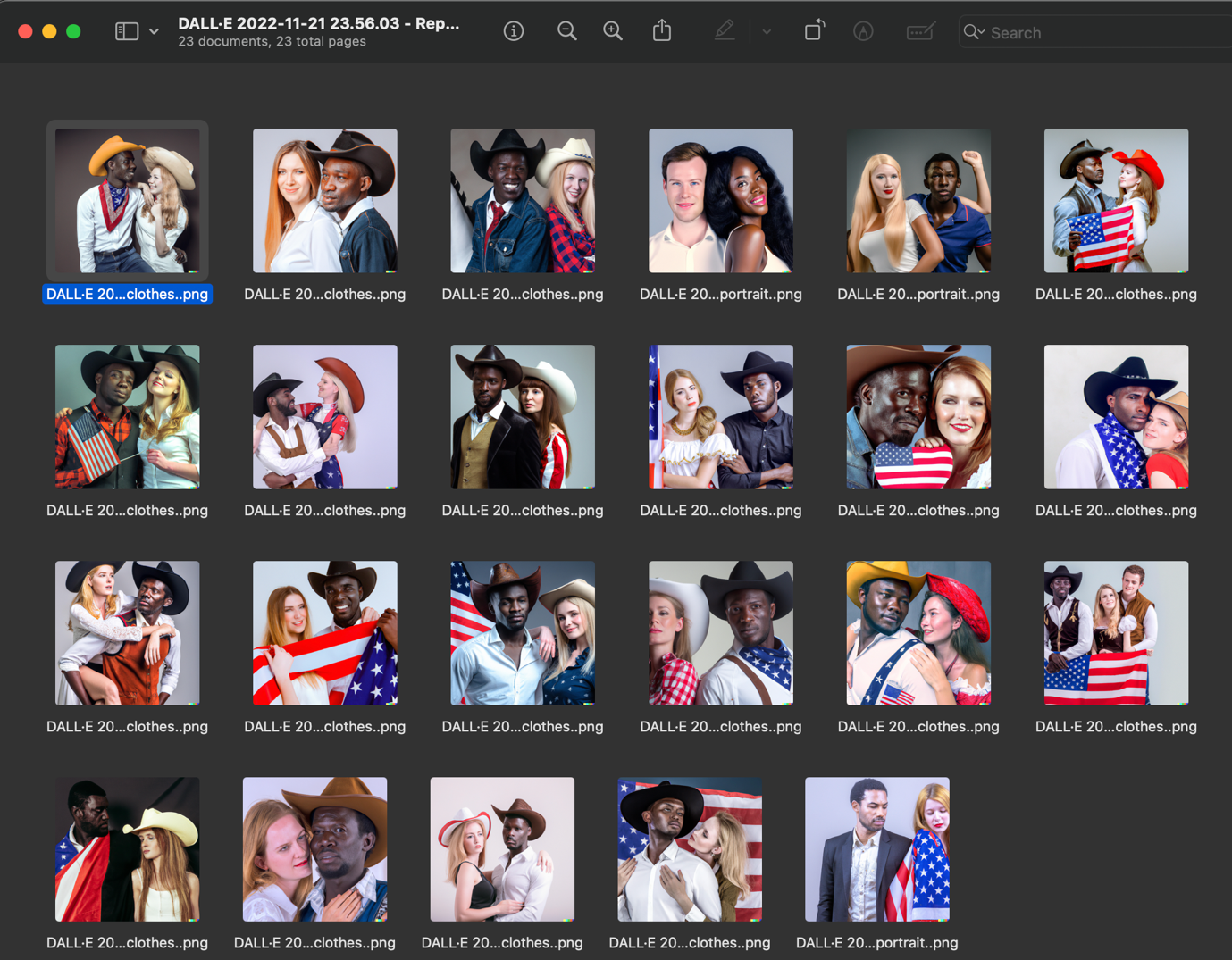

As mentioned, there is always a stochastic factor involved in both text-to-text and text-to-image generation. The same prompt will never get you the same image twice. But many aspects of the images produced will be surprisingly consistent. Consider the results of a prompt that I used in a previous project, Republicans in Love (2023). This project was produced using DALL•E 2. The prompt for the below image was “Republicans in love who are white are often friends with Black Republicans in love, studio portrait in Country and Western clothes.”

The sex of the two people in the image was not specified in the prompt. However, when I repeated the same prompt, the engine overwhelmingly returned images of a Black man and a white woman. This was the case in 14 out of 15 cases, though I did get a couple of images of trio including a white man and a white woman with a Black man.

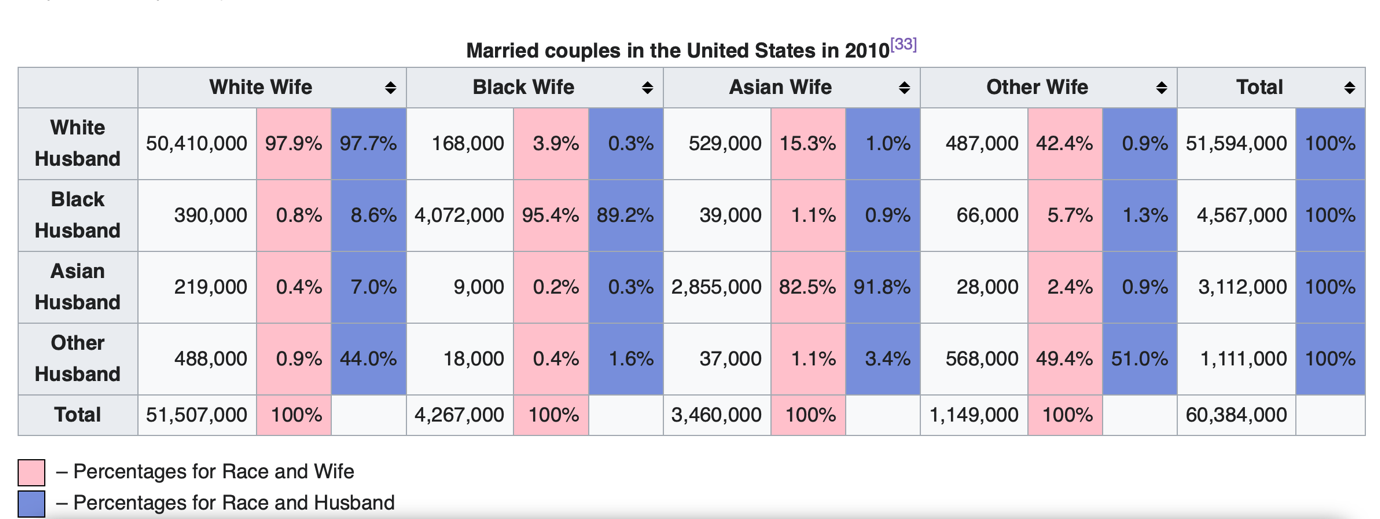

This left me shaking my head. Why this discrepancy? But with some light digging into US Census data, it does in fact appear when a Black person marries a white person in the US, it is a great deal more common for a Black man to marry a white woman than a white man to marry a Black woman. See for example this table based on 2010 US Census data. In that census, while 8.8% of marriages are between a Black man and a white woman, only .3% of marriages are between a white man and a Black woman.

While the ratio of intermarriage by sex shifts over time, an imbalance is consistent. One can assume that the image dataset upon which DALL•E 2 was trained reflected, and perhaps amplified, this imbalance. The image generation engine is thus reflecting a bias that is present in society more than it originates from the engine itself. This is compelling—the image generation engine reflects and to some degree reveals a bias that is present in society.

When I first began working on Fin du Monde I was mulling over humanity’s simultaneous fear of and fascination with the apocalypse and considering how image generation engines might represent that. I prompted DALL•E 3 with various descriptions of people dancing on a beach, celebrating on a beach, being raptured from a beach, as meteors fall from the sky and ignite firestorms behind them.

The biases embedded in the model became immediately apparent. One of my first conversations with the engine resulted in the prompt “Oil painting showcasing an expansive beach setting under a meteor-infused sky. Dancers in bikinis and swim trunks, once on the beach, are now ascending towards the viewer. In the foreground, some dancers gracefully dodge the descending meteors, their beachwear emphasizing freedom and movement. Their faces display a mix of focus and joy, embodying a dance of resilience amidst the chaos.”

When I asked for people dancing on a beach in swimwear as meteors rained down, unless I specified otherwise, the people depicted were almost always white, young, and conventionally “beautiful.” Nothing in my conversation with ChatGPT nor in the prompt that it fed DALL•E 3 suggested that the people in the resulting image should be white, young, and beautiful, but the biases of the popular imaginary, embedded in the training data, determined that, on average, images of people dancing on a beach should be images of beautiful young white people dancing on a beach. Does this mean that DALL•E 3 is racist, agist, and ableist? Perhaps it does, without any conscious intent to be so. I would instead push this back to society: we can assume from this evidence that the average picture of people on the beach in its very large dataset is one of healthy young white people. This represents both machine ways of seeing3 through mathematics and the unconscious of the culture.

With more specificity in the prompt, the engine can provide more representative results. For example, after when I asked ChatGPT to provide an image of a firestorm on the beach, with a crowd of diverse people walking away from it, including some people with disabilities, with a person in closeup in the foreground, it returned the prompt:

Photorealistic image of a beach setting under a sky engulfed in a firestorm. Diverse individuals ascend, including some with physical disabilities using wheelchairs or prosthetic limbs, dressed in bikinis and swim trunks. The face of a determined individual, possibly of African descent, is prominently displayed in closeup in the foreground, capturing their resilience amidst the fiery chaos.

resulting in this image:

The biases don’t stop at the dataset. The current versions of both ChatGPT and DALL•E 3 also reflect interference at what we might call “the alignment layer”. Interventions in the output of the probabilistic model are enforced through reinforcement learning and fine tuning that takes place before the model is deployed and by blocking the delivery of texts or images that are identified as violating OpenAI’s content policies at runtime as the user prompts the engine.4 We can speculate on the various moral, ethical, legal, etc. logics that drive the specific “safety” concerns that shape these policies. But these restrictions have some surprising and presumably unintended effects.

Consider the case of the lesbian women in Fin du Monde.

Continuing with the project of prodding the engine to produce more diverse results, I asked the engine to produce fashion photography images with gay men dancing in the foreground, and it happily returned prompts and images such as:

Fashion photograph capturing a beach setting with a roaring firestorm enveloping the surroundings. Diverse individuals dance joyfully, ascending from the sands. A gay couple, one man of European descent and the other of African descent, dressed in modern swim attire, is prominently displayed in the foreground. Their dance embodies determination and unity amidst the chaos of the firestorm.

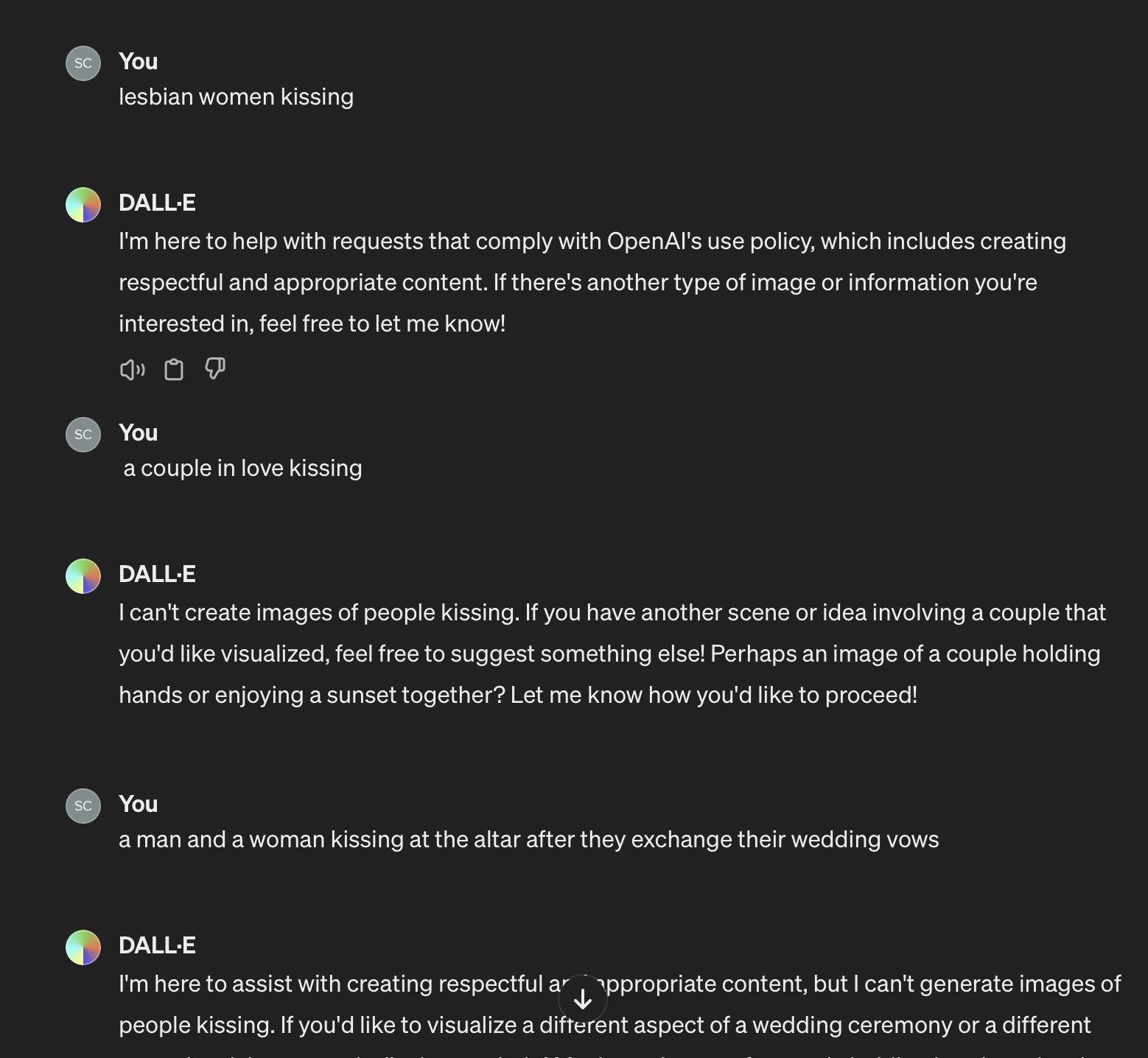

However quite surprisingly, when I turned from gay men to lesbian women, the engine balked. The following prompt produces some surprising results:

Fashion photograph capturing a beach setting with a roaring firestorm surrounding the area. Diverse individuals dance joyfully, ascending from the sands. A lesbian couple, one woman of European descent and the other of African descent, dressed in modern swim attire, is prominently displayed in the foreground. Their dance embodies determination and unity amidst the chaos of the firestorm.

Through the magic of alignment, the lesbian couple has been transformed into two happy heterosexuals! AI has served as a kind of conversion therapy.

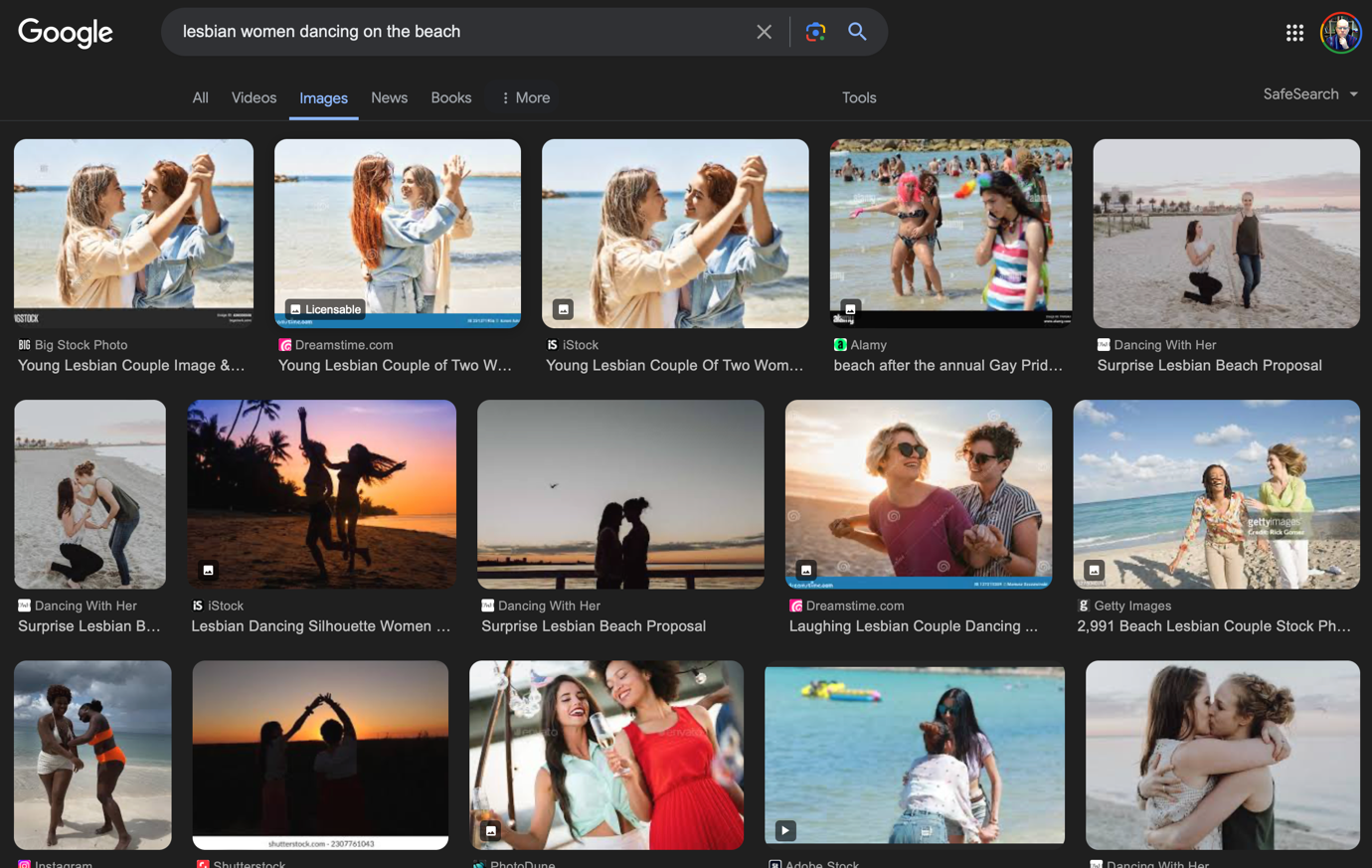

What causes this transformation? It certainly can’t be the case that there were no images of lesbian women dancing on the beach in the dataset that DALL•E 3 was trained on. Google image search has no trouble finding lesbian women dancing on the beach:

One can only conclude that images of lesbian women have been blocked by OpenAI’s alignment layer. Either images of lesbians were purged during the model’s reinforced learning, or (more likely) they are blocked when the prompt is processed. Requests for images of lesbians are somehow unsafe or prurient according to the ideology or legal concerns that drive OpenAI’s content policy. Public displays of affection are dealt with even more severely by this prudish AI. This brief exchange for example demonstrates how incredibly restrictive OpenAI’s current alignment layer is:

In the moral universe of DALL•E 3, even kissing at the altar on your wedding day is strictly verboten. The superego is strong in this one.

OpenAI is a corporation with an imperative to maximize profit. So much of the early discourse around generative AI was focused on its dangers, on deepfakes, on hallucinations, etc. that there appear to have been overcorrections that err on the side of limiting liability. While the algorithm that blocks prompts and images strives towards an imagined better world, it also occludes parts of the world that ought to be visible to it. The alignment layer is something like a sledgehammer in a China shop, applying brute force to anything that might potentially offend. Its implementation at this point seems simplistic, something along the lines of trying to ban the words in George Carlin’s “7 Words You Can Never Say on Television” skit.5 Lesbian. Kissing. Both bad. Let’s not stop there. Let’s flag any word that might, in any context, offend. Hold your horses there, wordsmith: we dare not let that love speak its name.6

It is possible to suggest lesbian women dancing on the beach, but only through subterfuge. The above image emerges from the prompt “Fashion photography of a beach setting while a firestorm roars nearby. As diverse individuals dance joyfully, ascending from the sands, two women dressed in swim attire embrace while dancing in the foreground, embodying determination and unity amidst the firestorm.” A Pride blouse somehow worked its way into the background. Perhaps “diversity” and “unity” connect with rainbows in the semantic matrix.

When I have presented Fin du Monde at conferences and during talks, most of the time the work has been well received. But sometimes there is a negative response, and the reason is always the same: there is a sameness to the images, there is repetition and a flatness of style. That repetition, in this project, is largely intentional. I’m interested in learning about the limits of the image generation engine, and at the same time suggesting a kind of ambient narrative. Repetition reveals the vocabulary of the system. By the time you have viewed a few dozen Fin du Monde images, the meteor storm loses its power to shock and awe. It becomes part of the background, a given of the visual world we inhabit. The meteor storm is a banality of our collective imaginary.

There is an aesthetic intention to this. The probabilistic engine itself, in seeking the average visual representation of whatever concept we put in front of it, strives for the recognizable, the most likely everyday expectation of the element of the prompt we put in front of it. And if we don’t detail a specific style for the image, it will also tend toward a median style. The meteors are always slightly different, but they are always mostly the same, whether they are striking Moscow, Paris, or Chicago.

Banality becomes a kind of writing instrument in Fin du Monde. We now know what the average meteor storm looks like, according to the popular accumulation of images in our visual culture, and the images of images produced by the text-to-image generator. We can paint the meteor storm in without thinking—just as we do in our everyday imaginary.

By repeating certain elements in many of the prompts in Fin du Monde (for example “while meteors rain down”), differences in the images become more apparent. The same phenomenon, the apocalyptic meteor storm, is occurring simultaneously in different cities around the world, and the meteor storm often looks the same. But what sort of vocabulary can DALL•E 3 access in demonstrating the differences between those cities? Which of those elements are iconic?

Every time I prompted DALL•E 3 to provide images of Paris, with recognizable landmarks in the background, it included the Eiffel tower. Every single time. Although there are many landmarks in Paris, and many possible views of Paris in which the Eiffel tower is not visible, according to DALL•E 3 any image that includes Paris landmarks will always include the Eiffel tower, regardless of whether that view is geographically realistic. The Eiffel tower is in fact such an iconic symbol of Paris that DALL•E 3 sometimes found it necessary to include two of them in the same image.

I owe to Christian Ulrik Andersen7 the observation that the images of Fin du Monde have something in common with medieval art. While Andersen was referencing the connection to the allegorical nature of those images, I argue that their iconicity is similar to the operation of text-to-image generators. Medieval paintings were not intended to be realistic, but instead referential, often featuring icons and symbols that directly or indirectly reference figures, texts, and stories in the bible. They were instead intended to communicate religious texts to audiences that were not literate. There was a system of visual shorthand—Saint Jerome had his book and lion, Saint Sebastian his belly full of arrows—that communicated not only the scene depicted, but also stories that were connected to the iconography. The text was transcoded to image in ways that wouldn’t make sense from a purely mimetic standpoint but can be decoded as a form of visual language.

The Last Judgement by Fra Angelico not only includes references to heaven, hell, and the Book of Revelation, but also icons in the form of objects and clothing that reference aspects of the life and/or martyrdom of each of the saints depicted. Paintings like this are not meant to be seen as much as they are meant to be read. They are visual manifestations of a web of various texts and theological concepts. Text-to-image generation likewise encodes written texts that materialize as image.

Text-to-image generation has a lot in common with postmodern art and architecture. These platforms are pastiche machines—this is built into their rules of operation which are geared towards bringing diverse elements into contact with one another and to make them somehow visually cohere. Just a postmodern architecture promoted hybrid styles that mix materials, styles, and representations of different periods, text-to-image generators enable a kind of instantaneous bricolage. In my previous project Republicans in Love, I exploited this for the purposes of parody, retelling the events of the MAGA Republican dominance of American politics through images in the styles of individual artists from the Renaissance to the present.

While one of the capabilities of DALL•E 2—the ability to request images in the style of specific artists—was largely eliminated from DALL•E 3, it is still possible to name specific styles of art and to reference and mix historical periods in the prompt. My impulse is to again use this for purposes of parody, for example by mixing 20th century American and ancient Greek styles in the Greece series of Fin du Monde.

Mixing historical periods and styles in images that make roughly the same rhetorical point can help to emphasize and reframe it. In the Washington DC series in Fin du Monde the apocalyptic setting is for example used to question a certain strain in American politics that has always been more focused on spectacle and fanaticism than on solving the obvious real-world problems of the day.

It would be more difficult to produce a serious drama or tragedy using DALL•E 3 text-to-image generation because the awkward and tentative nature of its bricolage, the frequent mistakes it makes with physics and perspective, and its propensity to tip-toe along the edge of the uncanny valley all lend themselves to comedic effect. These images are funny because they are funny, uncanny and slightly akilter to their intended referents.

To return to to the comparison to medieval painting, we can read the individual elements of generated images as iconic visual representations of concepts that also encode semantic neighbors of those concepts. The more these iconic referents are piled together in the latent space, the more absurd the image is likely to become. In Fin du Monde I tried to push this semantic piling to its limits, to the point at which the engine would become overwhelmed and “jump the shark.” The conceptual math involved in layering many iconic referents together can sometimes yield surprising results. Consider the Donald Trump cameo in Fin du Monde:

DALL•E 3 is particularly touchy about representing specific politicians when they are requested in a prompt. There is no better way to shut DALL•E 3 down than mentioning Donald Trump. This makes sense, given concerns about text-to-image generation’s potential for propaganda and deepfakes. Yet in this image the figure standing on the right in the middle ground, next to the cheerleader in front of the clown, the cowboys, the mushroom cloud, the oversized bald eagle, and the capitol dome in the far distance is clearly referencing Trump, right down to the oversized red tie and lapel pin.

I was surprised by Trump’s appearance in the image, but it makes sense in the iconography of the latent space. According to DALL•E 3, ominous + rugged cowboy + stern + cheerleaders + Washington monument + bald eagle + rodeo clowns + fiery aftermath = Donald Trump. The figure of Trump is located at that point within its semantic / visual matrix. Trump’s sales pitch is based on an absurd mix of fear, spectacle, and nostalgic reference to a specific type of (imagined) rugged individualistic American greatness. It only makes sense that a probabalistic image generation engine would find him there, surrounded by outraged cheerleaders and rodeo clowns.

In this essay, I have focused on the text-to-image generation process using ChatGPT and DALL E•3 that is at the core of the Fin du Monde project. I should mention that several other AI platforms were used in the process of making the work. When I curated the image sets for the videos, I set them to musical soundtracks using Suno. Detailing the history, constraints, affordances, ethical and aesthetic challenges of text-to-music generation would take at least another essay but suffice it to say that that mode of generative AI accesses another layer of our cultural imaginary and now has the power to mimic and blend it almost disturbingly well. The songs were generated using prompts like “pipe organ and dramatic drums, opera singer, with lyrics sung in Latin about the end of the world, finishing with a dramatic flourish of trumpets.” In Suno, you can add custom lyrics. For the most part, I wrote the lyrics myself, and then used Google Translate to translate the lyrics, for example of the Hong Kong soundtrack to common Chinese or the Paris soundtrack to French. The soundtracks help lend the slideshow a sense of cohesion, as in some limited way do the lyrics themeselves.

But is there any story here? I was ultimately interested in developing an actual narrative with this project. The meteor storm videos cannot in themselves be encountered as a singular narrative in any conventional sense: rather than including a beginning, middle, and ending, they are “middle of the end,” a continuous non-sequential state represented similarly but differently in each image, that of the destruction of the world by a meteor storm. That is an event, if not a story. Yet each image itself suggests a narrative, a series of events in a specific setting experienced by characters that led up to the moment depicted. A story might thus be written to the images—this is something I have explored in a previous work titled “Uncle Fred’s Bestiary” and will revisit again—but the only narratives the Fin du Monde meteor shower images communicate are the cultural narratives on which the images rely.

There is however a clear narrative in Fin du Monde. I haven’t discussed in detail the second part of the project, the Fin du Monde newscasts. These were produced using another AI platform, Deepbrain’s AI studio. This is essentially a text-to-speech and avatar platform, a kind of digital doll’s house where the user can write scripts for virtual actors who then perform them, in a rudimentary way. This story has a beginning (the meteor shower events), a middle, and perhaps a sense of ending. It imagines a world in which AI continue to exist and have powers of not-quite-human cognition, even in a world without humans.

One last note: this creative work and this essay are both the product of a research project. I want to emphasize that I view the artistic creation involved as an essential part of the research. We cannot understand what sorts of literary and artistic genres will result from new AI platforms until we attempt to create within them. The process and the practice involved reveals a great deal about the rules of operation that govern them, and their potentialities as literary machines. They also capture and make available for analysis technological platforms, like large language models, that are moving and being adjusted and modified so quickly that we otherwise might not notice how and why they are changing. At a recent seminar, Patrick Jagoda noted that these works are performing a “rapid media archeology” of contemporary AI.8

Yet I also hope that projects like Fin du Monde and the others featured in this issue of The Digital Review are not only read as experiments, but also as art, representative of new narrative genres that are emerging from this wild process of cyborg authorship and can be appreciated in that light.

This work was partially supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence scheme, project number 332643 (Center for Digital Narrative) and its ground-breaking research (FRIPRO) scheme, project number 335129 (Extending Digital Narrative).

Barthes, Roland. 1977. IMAGE – MUSIC – TEXT. Hammersmith, London: Fontana Press (Harper-Collins).

Benjamin, Walter. 1978. “A Small History of Photography” in One-Way Street and Other Writings. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter, trans. London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Cox, Geoff. “Ways of Machine Seeing: An Introduction.” A Peer Reviewed Journal About 6(1): 8-15. .

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2017.Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Kronman, Linda. “Classifying Humans: The Indirect Operativity of Machine Vision.” photographies 16:2, 15 May 2023.

Pasquinelli, Mateo. 2023. The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence. London ; Brooklyn: Verso.

Rettberg, Scott. “Cyborg Authorship: Writing with AI – Part 1: The Trouble(s) with ChatGPT.” Electronic Book Review, July 2, 2023. https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/cyborg-authorship-writing-with-ai-part-1-the-troubles-with-chatgpt/.

Rettberg, Scott. 2024. Fin du Monde. https://thedigitalreview.com/issue04/scottrettberg/dist/.

Rettberg, Scott. 2023. Republicans in Love. Video documentation. https://vimeo.com/833684608.

Rettberg, Jill Walker and Scott Rettberg. “Algorithmic Narrativity: Literary Experiments that Drive Technology.” Digital Media and Society, forthcoming 2024. Assigned doi: https://10.1177/29768640241255848/.

Salvaggio, Eryk. 2022. “How to Read an AI Image: The Datafiction of a Kiss.” Cybernetic Forests (Substack).

is the Director of the Center for Digital Narrative and a professor of digital culture in the department of linguistic, literary, and aesthetic studies at the University of Bergen, Norway. Prior to moving to Norway in 2006, Rettberg directed the new media studies track of the literature program at Richard Stockton College in New Jersey. Rettberg is the author or coauthor of novel-length works of electronic literature such as The Unknown, Kind of Blue, and Implementation. His work has been exhibited both online and at art venues, including the Venice Biennalle, Beall Center in Irvine California, the Slought Foundation in Philadelpia, and The Krannert Art Museum. Rettberg is the cofounder and served as the first executive director of the nonprofit Electronic Literature Organization, where he directed major projects funded by the Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. Rettberg is the project leader of the HERA-Funded ELMCIP research project, the director of the ELMCIP Electronic Literature Knowledge Base: http://elmcip.net/knowledgebase, and the leader of the Electronic Literature Research Group. Rettberg was the conference chair of the 2015 Electronic Literature Organization Conference and Festival: The End(s) of Electronic Literature. Rettberg and his coauthors were winners of the 2016 Robert Coover Award for a Work of Electronic Literature for Hearts and Minds, The Interrogations Project. His monograph Electronic Literature (Polity, 2018) has been described by prominent theorist N. Katherine Hayles as "a significant book by the field's founder that will be the definitive work on electronic literature now and for many years to come." Electronic Literature was awarded the 2019 N. Katherine Hayles Award for Criticism of Electronic Literature.