During the Holocaust millions perished without a trace. Today, can we give them a voice? Can Voiceless victims speak up for themselves? These questions sound absurd and they are at odds with the very foundation of history as an academic discipline: The Dead cannot speak; we cannot hear their voice; even more importantly, history cannot document their personal experiences and suffering. Are the Voiceless then forced to live on the margins of historical knowledge and practice?

Using contemporary technologies, we can create digital representations that give them voice - symbolically.

Giving symbolic voice to the Voiceless has been the main goal of In Search of the Drowned, a hybrid piece of digital scholarship and art. It is a piece in which I bring digital history, data science, and data visualization together.

There is one key thing that makes In Search of the Drowned a counter-work. I combine these apparently objective academic fields with the very subjective and personal fragments of my own family’s memory to document the suffering of the Voiceless - objectively. The blending of the objective and the subjective / personal is an act of transgression that goes against the accepted norms of history as an academic field.

The result of this blending is not only a digital counter-work; it is also a piece of speculative scholarship that urges historians to recalibrate the epistemological assumptions of their profession. In short, as a matter of fact we will never know what and how the Voiceless felt, but we can nonetheless reconstruct and know what they were likely to experience up until the last moments of their lives.

The main message of In Search of the Drowned is that history has to accommodate possibilities and the world of possibilities as epistemologically valid components of our knowledge about the past.

With this work I aim to show how data science, digital art, and data visualization can help historians discover this world of possibilities and make this intangible asset of our past visible.

In Search of the Drowned has three key components.

First, in a series of multimodal essays, I offer philosophical reflections on the voice of the Voiceless. I discuss themes related to historical loss, the collective experience of persecutions, as well as problems related to the representation of suffering in the past. Most importantly, I work out a new digital representation, the testimonial fragment, through which we can hear the voice of the Voiceless - again, symbolically. My essays will take you through an interactive and audio-visual journey where you will watch and hear survivors’ recollections, hear about family stories, and dive into the collective suffering of Holocaust victims.

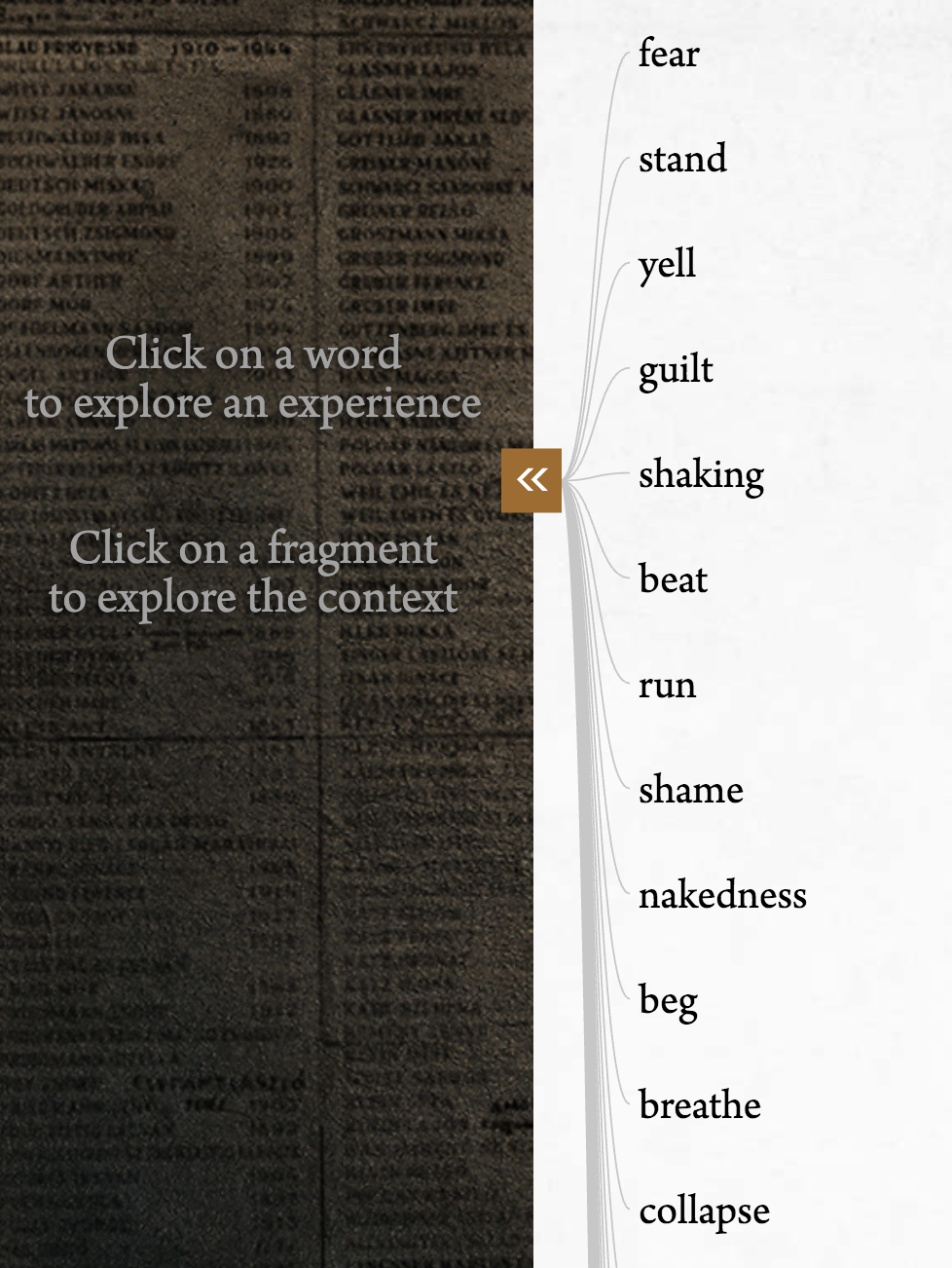

Second, In Search of the Drowned uses a hierarchical tree visualization to render testimonial fragments. These are short textual fragments that I retrieved from thousands of survivor testimonies using text and data mining. Testimonial fragments are pieces of the collective suffering that any Holocaust victim, including the Voiceless, was likely to face during persecutions. They are also meant to evoke the world of possibilities in which Holocaust victims lived their everyday lives during their persecutions. Through the hierarchical tree visualization you can browse hundreds of testimonial fragments and read or listen to them in the original survivor testimonies where they were found. The visualization of testimonial fragments allows you to “see and hear” the mental, emotional, and physical experiences that the Voiceless were forced to face. The visualization of testimonial fragments is in fact a digital transformation of thousands of survivors' testimonies; as a digital transformation it enables Holocaust victims to speak up and tell some and definitely not all pieces of their collective suffering.

Third, In Search of the Drowned features almost three thousands testimonies of Holocaust survivors from three major US collections: The Yale Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies; the USC Shoah Foundation; and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. You can read and listen to these testimonies and you can search them with sophisticated tools.

Below is a short video that summarizes In Search of the Drowned.

My essays are organized into three groups preceded by an epilogue and followed by a prologue.

The central theme of the first three essays is the last wish of murdered victims, often conveyed by the survivors: They asked posterity to remember them. I discuss the moral implications of this wish and argue that it involves two things. First, we have to document their voices, i.e., their mental, emotional, and physical experiences, even if this is literally impossible. Second, to approach these experiences, we have to rely on the collective voice of victims.

In the second group of three essays, I focus on collective experience itself. I argue that it is a set of possibilities that any victim of the Holocaust, including those belonging to the Voiceless, was likely to face. Through testimony excerpts I discuss what living in the world of possibilities that persecutions involved meant from the victims’ perspective. I also address how collective experience understood as a set of possibilities can be approached through the concept of recurrence. Through testimony excerpts, I make the concept of recurrence accessible to readers. In the last essay of this second group, I reflect on the collective experience of victims as infinitely complex and fundamentally different from our "normal" world.

In the last group of three essays, I address the problem of how to represent collective suffering. To elaborate an ethically informed representation, I again draw on survivors’ memories. For instance, in the first essay, I develop the concept of the testimonial fragment by pointing out how extensively survivors used fragment metaphors to describe their own past.

The collection of reflective essays concludes with an epilogue. Here, I address the tension between victims’ meaningless suffering and history as an explicable process. I point out the fundamental difference between persecutions from the victims’ perspective and from the perpetrators’ perspective, and argue that the Holocaust has two histories. One is centered around suffering, and the other one revolves around how and why the Holocaust’s perpetrators committed mass murder, and what this involved. I close the essays with the argument that both histories are needed but cannot be connected.

was born in Hungary. After studying philosophy and medieval studies in Budapest, he moved to England. In 2014 he completed a PhD in early modern history at the University of Oxford. Following his doctoral studies, Gabor was an assistant professor in digital humanities at the University of Passau in Germany. Between 2016 and 2020 he was a visiting researcher in the United States, at Yale University, and at the University of Southern California. At the moment, he is a research associate at the University of Luxembourg’s Center for Contemporary and Digital History (C2DH).