1. Introduction

Timeframing: Temporal Aesthetics in Digital Comics is a video essay that positions the juxtaposition of temporal vignettes — whether in film, video, digital comics, video games, or any other medium — as a distinct practice called timeframing that is worthy of study. The essay was created using a tool called Stepworks that I designed to encourage the exploration of this practice, which has significant connections to comics, along with its own unique qualities.

I encourage you to watch the video first (~20 min), and then to read on for some additional thoughts about the design of the tool used to create it, and the implications of timeframing for the ecosystem of digital narrative.

Timeframing: Temporal Aesthetics in Digital Comics was originally presented at the 2020 Electronic Literature Organization conference.

Download video (1.04 GB)

↓

2. Panels as Characters

The design of Stepworks, the tool used to create the video essay (and also employed in the speculative narrative Trina featured in this issue), derives from a point which is touched upon only briefly in the essay itself: that unlike traditional comics, timeframing imparts agency to panels in a split-screen composition. Panels become not just passive organizers of visual and story, but active agents that “know” who and what they represent, behaving accordingly.

Stepworks makes this phenomenon literal by treating each panel as a named character in the “story” of the presentation you are using the tool to build. The script of a Stepworks presentation is thus made up in part by actions taken by these panel-characters. When a character “speaks,” words appear within their panel. When they share an image or video, that media appears cropped within their panel’s bounds, able to be pushed, moved, and resized as new panels enter the scene.

Seen in this light, the Timeframing essay is effectively a story told by six characters: myself, another character named Carston who delivers the major titles, and four more (Moira, Tuan, Keira, and Russell) who feature the bulk of the project’s media quotations.

View the raw script for the essay (JSON format)

Perform the essay yourself (Stepworks + 1.37 GB of media)

↓

3. Restaging Stories

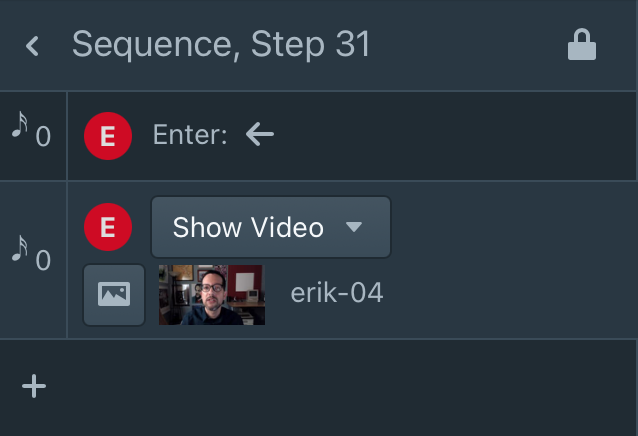

I believe that treating panels as characters makes split-screen compositions easier to build. Instead of repeatedly creating masks, specifying coordinates, and choosing media, as one might do in a program like After Effects, the author instructs a character to enter from a specific direction and show an image or other media, as seen in the Stepworks screenshot detail below.

Describing media presentations in this way also has a secondary effect which is just as integral to Stepworks’ design. By abstracting complex split-screen layouts into discrete actions taken by panel-characters, the “story” of a Stepworks presentation becomes one that can be easily restaged in any number of forms. To emphasize this point, I’ve created three alternate renderings of the essay:

- A “choir” version you can perform yourself which assigns every character to fixed, equally-sized areas of the screen, making it easier to understand what each is doing;

- A screenplay version describing the actions and dialogue of the six panel-characters (“CARSTON enters screen left, majority width, his words displayed as white text on a black background...”);

- An Observable visualization displaying in a table format the text and visual content featured by each character across the presentation’s 139 steps.

My aim with these examples, and this discussion, is to demonstrate that the practice of timeframing goes beyond split-screen composition to imply an approach to digital storytelling that, in its emphasis on character agency, promises greater portability of content and malleability of form than is typically possible for digital rich media narratives.

In Stepworks, I’ve tried to design an open format for representing narrative that is simple, flexible, and extensible, able to represent the actions of characters across a wide variety of stories and presentation styles even as it makes no attempt to represent the mechanics underlying those actions. Even in the case of an extremely sophisticated video game, it should be possible to create a transcript of narrative events in this format which could then be rendered in multiple ways: as a digital comic, analytical visualization, or something else entirely.

In this way, the essential story beats of any one of a number of experiences have the potential to become portable, able to be relocated into new application contexts and reformatted accordingly. Conversely, applications which support the import of stories structured in this way gain the ability to load similarly formatted content from any number of sources, including user-generated content. An digital ecosystem which handles narrative in the manner implied by the practice of timeframing may therefore increase the reach of individual stories, and the longevity of individual applications, beyond the “one-off” designs which are still quite common in the digital narrative arts. Surpassing my personal affection for comics and split-screen composition, it’s this potential that animates both my study of timeframing and my tool-building to support it.

■