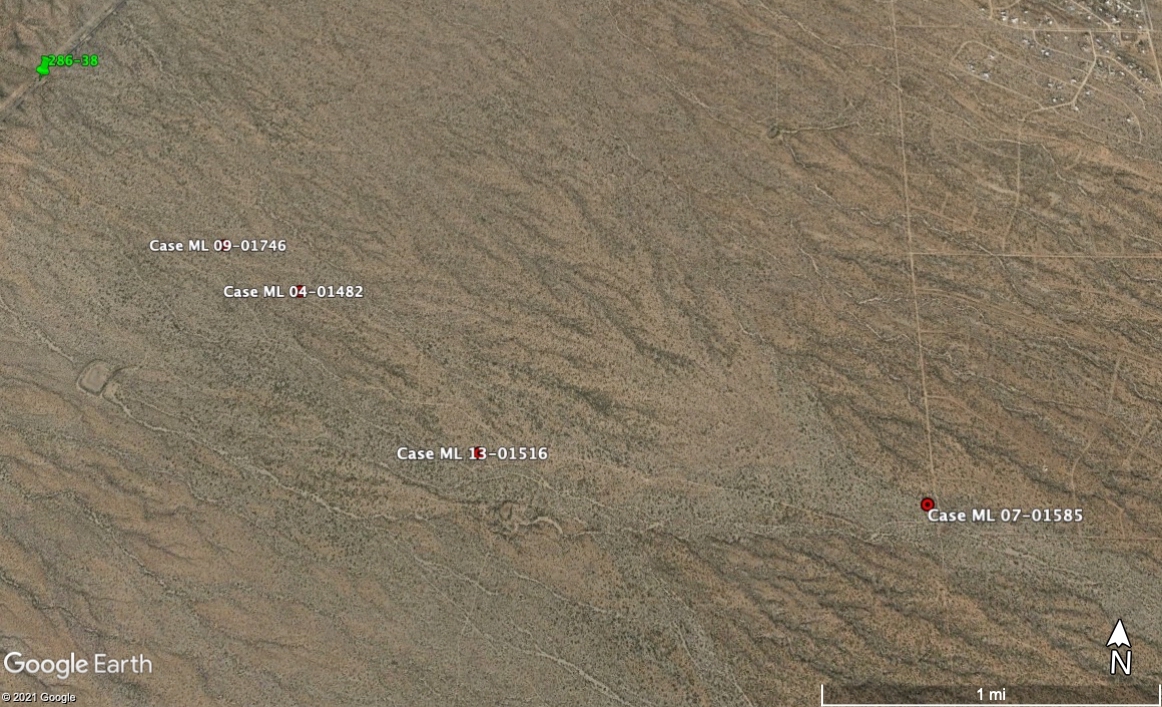

Ricardo Aguilar Cruz was found on February 2, 2007 on the outskirts of the Tumacacori Mountains. On the edge of a pipeline road, and in clear view of I-19, Ricardo’s body was recovered after about a day according to the Office of the Medical Examiner. Accessible with an all-terrain vehicle, the spot is both extremely close to inhabited areas and completely removed. It is a remote site with grand views of difficult mountains that are part of the Coronado National Forest. The site, like many others, is full of contradictions about the isolation of migration and the close proximity to assistance.

Throughout Vistas de la Frontera are the names of the person who was recovered overlayed on the environment in the video. The inclusion of the name is part of memorializing the individual. Thousands of migrants have died crossing the desert and while looking at maps of those deaths is helpful, it often reduces these deaths to just numbers. By placing the name on the landscape, it shows how each place is marked by that death. In the videos, the name is part of the environment itself – it is part of the intertwined nature of loss to the elements. This is an illustration of how the use of interactive technologies creates what Lev Manovich calls a “dataspace” wherein an “immaterial layer [is placed] over the real space” (Manovich 227). While Manovich is writing about augmented reality systems via locative technologies, the idea of a dataspace is an important one to both seeing and experiencing spaces of memorial that have been digitized and made accessible. The space is real, and its digital representation is not a live feed, but a video. The intersection of the real and its augmentation is part of illustrating how the natural world is marked by the loss of a person in a particular space, both literally through decay and symbolically through the act of memorialization. The videos, as well as other forms of memorial, allow each site to become a place of reverence worth revisiting.

Accessing the sites central to the creation of the “dataspace” demanded bridging the divide between maps on the computer screen and the realities of the Sonoran Desert. Exploring the desert – even the interactive maps provided by Humane Borders – gives users an awareness of the immensity of the desert but fails to capture the reality of navigating that space. In this way, the desert becomes an interactive and exploratory space, but its dangers never cross into the physical reality of the user. Safely navigating the desert, particularly one that has been weaponized, depends upon many overlapping privileges: access to water, GIS data and maps from Google Maps, GPS units, all-terrain vehicles, and knowledgeable guides.

Humane Border has made the data from their migrant death map available for download on to Google Earth and handheld GPS units. Overlayed with red dots and mile markers in some areas the maps serve as a point of entry. Roads are often visible on these maps, but the satellite imagery available can be years old and not reflective of the contemporary reality of the area. Worse yet are the locked gates that bar travelers from entry without any warning or rationale.